Despite having strong pros and cons, badge engineering is a staple in automotive development. Here, we are going to delve into the details of such an intriguing strategy

Stellantis took everyone by surprise in summer 2022 during the Speed Week. The event hosted by Dodge introduced several upcoming plans and releases, but the most important one was surely the Hornet. Not only because of its unique combination of performance and value, but also because it is closely related to the Alfa Romeo Tonale above. Now, what does it mean when cars have such a relationship?

Badge engineering has a self-explanatory name. It is an industrial strategy where a given product receives new logotypes to be sold by another company. In theory, it is hard to resist: one company gets an all-new product ready to sell while the other enjoys additional production demand. The thing is, there are several reasons why that can be difficult to have success in practice. We are going to take a look at all that.

How can badge engineering help?

According to Autoblog, developing an all-new car can cost an adjusted $7.7 billion. That is a lot of money even for multinational companies such as GM or Toyota. They can invest that money over years, sure, but they are always working on several new projects at once. It is easy to understand that they may not have such amounts at certain times. That is the main reason they resort to other companies for cooperation.

In other cases, it is a matter of worthiness. Some car types are great additions to any lineup, but everyone knows they will not sell in massive quantities. And, as you can imagine, no one wants to start any venture that will most certainly lose money. In those cases, finding a business partner is interesting because their cost sharing makes the risks lower. The project becomes more viable from many points of view.

There has been a third main purpose. Companies like GM operate with distinct brands depending on the region. Even though each one has its own design identity, there are ways to develop a car model that can be adapted to most of them. Badge engineering is especially useful when creating generalist cars because the manufacturer can offer them around the world with a minimal investment in design adaptations.

Badge engineering in practice

The textbook interpretation consists of changing the logotypes from one brand to the other with nothing but the necessary adaptations. This article has a section with detailed examples below but, for now, let us mention one case here. In the early days of FCA, Lancia would import the Town & Country from Lancia to sell in Europe. In order to save costs, the Voyager appeared in 2011 with nothing but changed logos.

Whether we talk about different companies or branches of one company, that is essentially one of them buying cars from the other to resell as their own. It is the easiest and quickest way for a company to get a new car ready to go on sale. In Lancia’s case, that came in handy because it needed to replace the Phedra but the parent company, Fiat, was focusing its capital on concluding the merger with Chrysler.

Now, we all know that there is no perfect strategy in the industry. If you research that Lancia case, you will see that the Voyager and many other rebranded cars of that same time never sold well. Over time, the industry learned that being that radical almost never brings favorable sales results. The next topic on this page is going to cover the main reasons according to the history of several examples of rebadged cars.

What problems may happen?

Let us illustrate with an exaggeration: imagine that Ferrari starts selling a Land Rover SUV. It would appear on Ferrari’s website, rebadged with the horse, maybe even come in red. It would have the same quality as any other model Land Rover produces, and Ferrari would sell it as any other of its cars. What would that look like? We know the most likely answer to that is “weird”, but how? Could you describe exactly how?

There is the fact that those companies normally work in different segments, sure. The main reason for that feeling, however, is that their images are different. In short, Ferrari is about dynamism and emotion while Land Rover offers ruggedness with elegance. It is virtually impossible to make one car comply with both guidelines. Imagine adapting an existing car from one company to the other at a moderate cost.

Those differences affect the entire car. Each company has its own parameters regarding handling, power delivery, suspension settings… That is why people prefer one brand over the others. Besides, the Internet can show the origins of any car in seconds. That is why the original concept of rebadging car models never truly took off. In a way, ignoring all those emotional factors is an insult to buyers’ intelligence.

Co-development to the rescue

Fortunately, that problem was easy to solve, and the industry quickly realized that. The common practice now is for the two companies to work together to some extent. The “clone” now comes with at least a few exclusive items, especially visual ones. That is the case with front grilles, wheels, and internal trim. Upscale models may go further and receive exclusive headlights and taillights, and infotainment software too.

In other words, it was necessary to dial down that strategy to make it successful. That lowers its potential profit as well, but that is just the way it is. The relevant implication here is that the initial notion of badge engineering is purely theoretical; in practice, it rarely sells as well as it should. The best solution is to develop joint projects leaving enough room for each company to express key aspects of its image.

If you want another brief example, take the 86 and BRZ coupés. Toyota and Subaru created them together and that is easy to see. However, they also had enough freedom to express their identities through those items: front grilles, wheels, internal trim… Speaking of Toyota, that strategy of automotive badging turned out so well that, later, it joined BMW to develop the Supra and Z4. But let us focus on some examples.

Easy way into new markets

That Lancia example of some paragraphs above is only one of many. Releasing a new car model is already risky on its own, let alone when it is the first of its maker in a new segment or a new region. It is common for companies to rely on the expertise of others to minimize their risks of problems. While situations like Lancia’s are common, there have been others where rigid badge engineering brought good results.

Suzuki tried its chances in South America in the 1990s, mostly because the Brazilian market had just lifted an import ban. However, subsequent economic turmoil ended making the Japanese automaker leave the country in a few years. The Vitara SUV had a much better performance when Chevrolet began to sell it as Tracker. In fact, it used that nameplate in two other generations despite coming from internal projects.

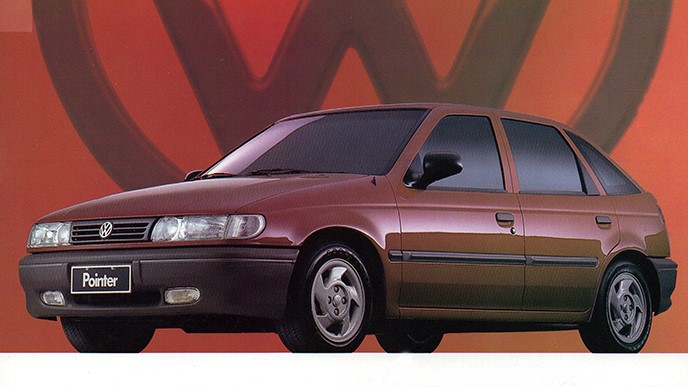

Ford and Volkswagen went through a weird situation in Brazil in the 1980s. Autolatina was a joint-venture focused on making them stronger in the region, but it had mixed results. Basically, all the cars created by one and sold by the other failed in the market. The Pointer, for example, did not turn three years old. The biggest complaint was that those “hybrid” cars did not correspond to the brand that was selling them.

Badge engineering in the USA

You know how cars often come in several trim levels? Base, intermediate, luxury, sometimes a sporty one… Chrysler, Ford, and GM used to do that in a unique way. If you wanted a midsize sedan in the 1990s, there was the Plymouth Breeze, for example. But if you needed something fancier, the same car would become the Chrysler Cirrus. In case you prefer a sportier look, the maker would offer it as the Dodge Stratus.

USA automakers had so many brands that they ended up acting as trim levels for the same cars. There was some distinction too, sure, but not that much. GM kept some engines exclusive to Pontiac or Oldsmobile, for example, but that did not last long. Once the oil crisis took place, those companies had to cut costs as much as possible. That ultimately forced them to streamline their whole branding strategy.

Over time, those companies reached an internal compromise. They phased out some of those divisions to execute a better strategy with the others. Nowadays, they are using more flexible strategies like modular platforms. That enables the company to use few mechanical components on many models while keeping more of their creation budget focused on external design, internal trim, and overall image work.

World car projects

In the 1980s, globalization was all the rage, and the car industry wanted in. GM became famous for the J platform, but the goal was general: to create world cars. In other words, one car model that could be sold in many different regions with as few changes as possible. At first, GM’s project reached the entire world under many brands with only a few body styles, and minimal cosmetic changes to suit each division.

The original idea was brilliant. It would minimize development cost and time and maximize integration between factories. Since most components were the same for all models, the company could balance its production flow by having underused facilities help others with excessive demand. We can consider the first Ford Focus as another example, even though it came in the 1990s and had a narrower scope.

Here, people noticing the “trick” was not an issue because it was never a secret. The real problem was the cars’ image once again. The Cadillac Cimarron, for example, was ridiculed for offering too little above the Chevrolet Cavalier to deserve its badge while costing much more. In the end, the car industry realized that it was more productive to work with broad divisions, such as by continent, than to unify everything.